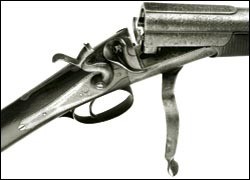

Reviving the trend for hammerguns

Who would have thought that at the beginning of the 21st century hammerguns would be having something of a renaissance? There has always been a great interest and enthusiasm for these older types of guns in the US, but in recent years that interest has become resurgent in the UK. Not only are hammerguns being increasingly seen in the shooting field, they are also starting to appear in side-by-side competitions. Gunshops and dealers are starting to take a greater interest in hammerguns, too, and, should anyone be in any doubt that the hammergun is back in fashion, in 2004 James Purdey & Sons launched a new square bar-action hammer ejector.

Despite an undeniable blend of form and function, and notwithstanding their growing popularity, there are many sportsmen who have been brought up using hammerless guns and who consider exposed hammers to be unsafe. Of course, there are undoubtedly special dangers associated with the handling of a hammergun: a thumb slipping from a hammer in the course of cocking or un-cocking; and even less likely, pulling the wrong trigger when un-cocking a loaded gun. It is for these reasons that the safest way to handle a hammergun isto do so with the gun pointed straight up at the sky. The handling of any type of gun, be it a hammergun or hammerless, requires due consideration to safety since the only safe gun is an unloaded gun ? not just a gun that is believed to be unloaded, but one that can be seen to be unloaded.

Safety concerns

No gun, even those fitted with intercepting safety sears ? perhaps the most effective safety mechanism wherein a lever prevents the fall of the hammer until released by the pull of the trigger ? is totally immune from accidental discharge when loaded and cocked, since mechanical failure can render any safety mechanism ineffective. However, the misconception that all hammerguns are mechanically unsafe betrays ignorance of the workings of the hammer mechanism.

The lock of a hammergun has three positions: cocked, half-cocked and fired or hammers down. Hammerguns are capable of firing with the hammers in two positions: when the hammers are cocked and when the hammers are down. In the first instance, firing the gun is achieved in the conventional manner by pulling the trigger, which lifts the nose of the sear from a notch cut in the tumbler and allows the hammer to rotate under the force of the mainspring to hit the striker. In the second, if the nose of the hammer is resting on the striker a blow to the hammer would cause the gun to go off. So for the purpose of safety a third or intermediate position is provided, known as the half-cock position, in which the hammers are raised off the strikers.

In the half-cock position the nose of the sear engages in a deep slot in the tumbler, preventing the trigger being pulled and holding the hammer out of contact with the striker. Equally important, this position prevents accidental discharge as a result of loading the gun with the hammers down. Assuming that the nose of the strikers protruding from the action face has not prevented the gun from being opened, closing a gun loaded with fresh cartridges on to protruding strikers will have dangerous consequences.

Hammerguns tend to fall into two types: the earlier non-rebounding locks and those having rebounding locks. With non-rebounding hammerguns it is necessary to pull manually the hammers back to half-cock before unloading, while in the rebounding mechanism the hammers return automatically to the half-cock position after hitting the striker as a consequence of the gun?s clever lock mechanism design.

Birmingham born

The rebounding lock originated, like so many other landmarks in the history of gunmaking, from the Birmingham gun trade. The man most often credited with its invention was the well-known Wolverhampton lockmaker John Stanton. But Stanton?s was not the first mechanism to receive protection by a patent. That honour belongs to William Bardell and William Powell from Aston, Birmingham, with patent No. 2287 of 6 September 1866. However, Stanton undoubtedly takes the credit for the type of rebounding lock almost universally adopted by the English gun trade and found on most hammerguns encountered nowadays. Stanton produced three designs.

The first, No. 49 of 8 January 1867, received only provisional protection and used an external spring to lift the hammer to half-cock. Very shortly after this he secured a second patent, No. 367 of 9 February 1867, in which the hammer is returned to half-cock by the mainspring. This he achieved by lengthening one limb of the mainspring the top in a bar-action lock and the bottom in a back-action lock ? off which the tumbler bounces. And it was this design that was widely adopted, appearing in both new guns and as conversions to existing locks. In his third patent, No. 3774 of 30 December 1869, Stanton reverses the location of the projections on the mainspring limbs for bar-action and back-action locks, adding a characteristic curve to the end of the spring.

In the hands of an experienced and proficient Shot, the hammergun was an accomplished firearm. One of the greatest exponents of the art of shooting a hammergun was Earl de Grey the 2nd Marquess of Ripon. Widely acknowledged as one of the greatest game Shots of all time, his recorded lifetime total was a staggering 556,813 head of game and Earl de Grey normally shot with a trio of Purdey hammerguns. Shooting was his passion and his lifelong quest was for perfection in his favourite sport, so much so that he practised for hours with his loaders to the point where he is recorded as having had seven dead birds in the air at one time. So strong was his passion for shooting that on 22 September 1923, having killed 51 grouse on a single drive, he dropped dead in his butt while the last birds were picked.

So the rebounding lock represented a peak in the design of the hammergun mechanism. It offers a considerable advantage in terms of safety and convenience since the hammers rebound instantly and automatically to the safe half-cock position after hitting the striker, from where they are also prevented from moving in the event of an external blow. It wasn?t necessary to remember to put the gun manually to half-cock for loading and unloading, since upon firing the hammers automatically go to the half-cock position, thereby reducing the danger associated with hammers-down loading, which was a constant worry with the older non-rebounding locks.

An early solution to this problem that pre-dated the invention of the rebounding lock was the automatic half-cocking mechanism seen on pinfire guns, which lifted the hammers to half-cock as the gun was opened. This was necessary since it was not even possible to open the breech when the hammers were down on the protruding pins of the fired cartridges. In terms of the evolution of the hammergun, the rebounding lock was surpassed only by the hammer ejector mechanism, and that, as they say, is another story.