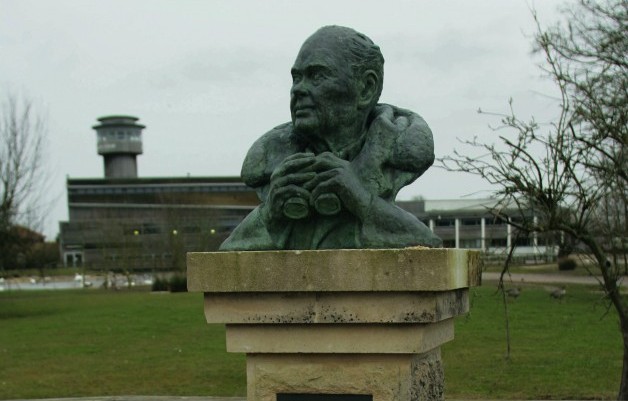

Father of the conservation movement

The conservationist and painter Sir Peter Scott was obsessed with wildfowling, a fact often airbrushed from accounts of his life by those embarassed by it, writes Tim Bonner

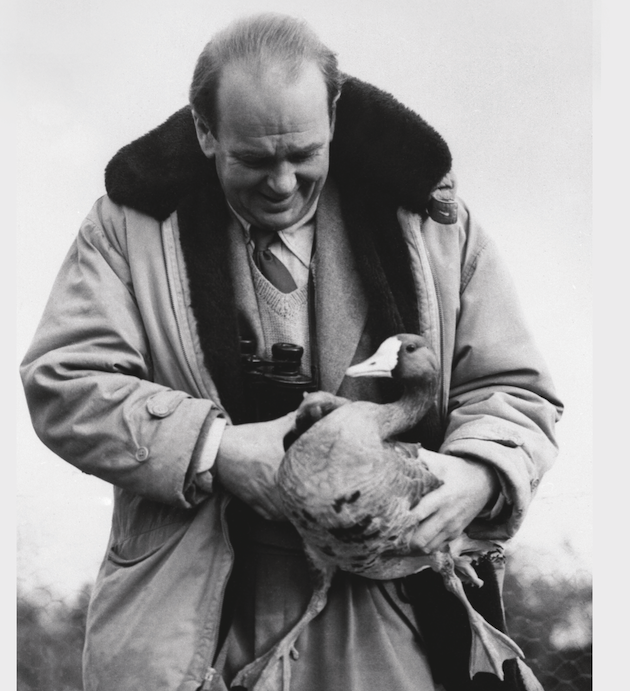

Sir Peter's experiences as a wildfowler directly influenced his work as a conservationist

I am not a great one for conspiracy theories, but every now and then you come across an omission that is repeated so often and so consistently that it can only be a result of an attempt to deceive, whether conscious or unconscious. One such involves the life of Sir Peter Scott who, among other things, was author of two of the finest books on wildfowling ever written and an obsessive punt-gunner and pursuer of geese. He was, of course, also a renowned painter of wildfowl, drawing on his experiences hunting duck and geese, and went on to record an extraordinarily eclectic series of achievements, most notably as a founding father of the conservation movement both in the UK and worldwide.

In Morning Flight, his first book, he describes shooting his first wildfowl, a snipe, on the Ouse Washes while an undergraduate at Cambridge. He goes on in both this book and its follow-up, Wild Chorus, to describe his growing expertise in the pursuit of duck and geese, including some enormous bags of pinkfeet shot inland under the moon in Lincolnshire. After graduation, he lived, shot, painted and started a wildfowl collection at the lighthouse at Sutton Bridge until joining the Navy at the outbreak of World War II and seeing distinguished service.

At the end of the war, he moved the focus of his operations from Sutton Bridge to Slimbridge in Gloucestershire on the banks of the river Severn, where a flock of whitefront geese traditionally overwintered on land belonging to the Berkeley family. The marshes had long been preserved and lightly shot, which was why the geese came back year after year. Shooting continued at Slimbridge after Scott set up the Severn Wildfowl Trust (later to become the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust — the WWT) and Scott himself took part. He continued to shoot at least into the 1950s, according to his biographer, Elspeth Huxley, including wildfowling trips to Ireland and Hungary, where he shot some large bags of geese.

References removed

The strange thing is that you can search the biographies of Scott on the websites of the conservation organisations he founded, such as the WWT and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and even Wikipedia, and you will find just a single reference to wildfowling and none on shooting. According to Wikipedia, as well as being a conservationist Sir Peter was a “painter, broadcaster, author (more than 30 books written and illustrated), global traveller, war hero and champion sportsman (in skating, dinghy racing and gliding)”, but not, apparently, a wildfowler. The WWF also lists his achievements as: “An Olympic yachtsman, a popular television presenter, a gliding champion, a painter of repute, a naturalist, a skipper in the America’s Cup, the son of a national hero, the holder of the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry and the founding chairman of the WWF.”

Beatrice, a former canal boat, became the floating HQ of the Severn Wildfowl Trust. Sir Peter pictured, centre) was in command

Some have even tried to suggest an early Damascene moment in Scott’s life when he turned his back on wildfowling, as if his continued involvement was incompatible with his role as an architect of the conservation movement. One blogger has attempted to suggest that an incident from 1932 that Scott records in his autobiography, The Eye of the Wind, was a turning point. After shooting a bag of 23 greylags, he wrote: “Among them were two wounded ones, and as soon as we had picked them up, we hoped that they might not die.”

The reason he did not want the greylags to die, however, is very obvious to anyone who has read the autobiography, because at the time Scott was starting his collection of wildfowl at Sutton Bridge and these two geese were pinioned and added to it. To suggest that this incident, at least 20 years before Scott actually hung up his guns, marked even the beginning of the end of his wildfowling career is pure nonsense. In fact, some of his biggest bags of geese were still to come, including a trip to Hungary in 1936 that yielded a bag of more than 350 whitefronts to his own gun, including 103 in one morning.

Mixed messages

It does have to be said that in the post- war years Scott himself was not entirely straightforward about his attitude to shooting. He was certainly still shooting big bags of geese in the late 1940s and early 1950s, including trips to the Wexford Slobs in Ireland. Almost simultaneously, however, he was writing to ex-employee and professional east coast fowler Kenzie Thorpe saying: “Like me, you’ve shot enough geese now.”

Wildfowling: Morning flight

Wildfowling: Morning flight: A morning’s flight on a desolate marsh is the highlight of Richard Brigham’s sporting year.

A guide to wildfowling in the UK

Wildfowling: Whether mallard, pintail or teal, those who want to shoot the different duck species are spoilt for choice.

In The Eye of the Wind, published in 1961, he describes another incident, presumably on the Severn estuary, where he and a party of guns wounded a goose that landed on an unreachable sandbank where it took some time to die, and states “I no longer shoot”. When he actually put down his guns is another matter and there are persistent suggestions that he continued to shoot for some time after the “official record” suggests he stopped. There is no doubt, though, that Scott did reach a point where he personally did not feel the same urge to hunt duck and geese as he had. There is also no doubt that he felt it easier to deal with some of those he was working with on conservation projects while not actively engaged in wildfowling and shooting. What is absolutely certain, however, is that in the decade before the war, and for many years afterwards, he was not just a casual wildfowler, but a committed and obsessive shooter of duck and, particularly, geese, and he killed more fowl than most of us will ever come close to. His bags of pinkfeet, including the 88 shot under the moon in Lincolnshire, and described with such pride in Morning Flight, would be considered excessive now, when the pinkfoot population is vastly greater than it was in Scott’s day.

What is also unarguable is that his experience as a wildfowler directly influenced his work as a conservationist, certainly much more than his experience as a dinghy sailor, ice skater or glider pilot. In fact, it is quite clear that it was his discovery of wildfowling on the Ouse Washes and the Wash while an undergraduate at Cambridge that sparked his interest in wildlife and led directly to the foundation of the WWT, and subsequently the WWF. He was brought up a city boy in the shadow of his hero father, who perished in Antarctica without setting eyes on his son, and was very close to his artist mother, who mixed in London’s smartest circles. By his own admission, the closest he got to the natural world during his early life was being taken to feed the ducks and geese in St James’s Park. His time at Oundle School in Northamptonshire gave him a first real taste of the countryside, but it is impossible to read his early work without understanding that it was from wildfowling that his love of nature and its conservation sprung.

In the foreword to my great-uncle Ian Pitman’s book on wildfowling And Clouds Flying, written in a prisoner-of-war camp, smuggled home and illustrated by Sir Peter, who was a friend of his, Ian muses that a time may come when he would choose to put down his gun and just watch the wildfowl he so loved. He did not live as long, or shoot as much, as his friend, and never actually reached that stage. The fact that Sir Peter did is no excuse to write out of his history the sport that he pursued obsessively and that laid the foundations for the extraordinary career that would come after.

DRAWING ON HIS EXPERIENCES

Sir Peter Scott wrote and illustrated more than 30 books — among them what are acknowledged as two of the finest books on wildfowling ever written. The first, Morning Flight, published by Country Life around 1935, included a proud description of shooting a bag of 88 pink-footed geese, while its follow- up, Wild Chorus, relates his increasing expertise in shooting duck and geese. He later became renowned as a painter of wild fowl.