Will cross-breeds ever rule in the field?

Sometimes, diluting a pure-bred with a bit of something else produces a working gundog that is ideally suited to a particular job, says Jackie Drakeford

A bobbery pack can do all sorts of jobs, even under the 2004 Hunting Act

While I appreciate the wealth of pure-bred working gundog breeds, I would not hesitate to use a cross-breed working dog if it gave me an extra edge for a particular job. It takes months to train a gundog properly and minutes to ruin one, so it often pays to create a type of dog willing and able to work outside strict guidelines without disgracing us in the shooting field, rather than making criminals of those we have trained so hard to be steady. This is particularly appropriate with vermin shooting, where dogs often have to use their initiative rather than waiting for direction — a genie that doesn’t go back into the bottle.

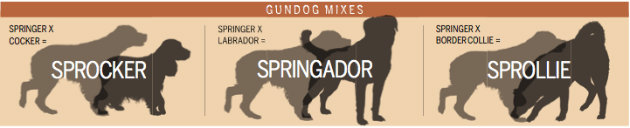

As well as the work these edge- of-control dogs do, the terrain and undergrowth they have to do it in often suit certain crosses rather than any pure breed. Deep, clinging clay mud, dense thorn thicket, unfriendly fences and ditches all present exhausting challenges through a working day. Where a cocker might struggle and a springer be too large, a sprocker fits between the two. It is still a spaniel, with all the charm, talent and drive we expect.

The verve and sparkle of a springer absorbed into a Labrador creates a dog with patience as well as substance, a tougher hide, and a tail that is less likely to be damaged if left undocked. Border collies can be trained to do nearly any canine job, but their sensitivity to sound is often their undoing when guns are used. Sprollies are far less likely to be affected. More biddable than pure spaniels, with a strong desire to return as well as hunt and retrieve, the OCD nature of the collie is calmed while the work ethic remains vast

A sprocker is still a spaniel, with all its talent, charm and drive

Mixed (bobbery) packs

With careful cross-breeding, the whole is often greater than the sum of the parts, if only for that particular job. Sometimes the task is such that we do not want a high- octane dog for it, rather in the way that a Land Rover suits where a Maserati will not.

Mixed (bobbery) packs for driving foxes out of cover to waiting Guns now labour under severe legal restraints. Under the 2004 Hunting Act, only two dogs at a time may be used, except in Scotland, where a pack can still be deployed. For the rest of the UK, only rabbits and rats may be hunted using more than a couple of dogs. Therefore the cross-breed is created to fulfil disparate needs, where previously there was the luxury of using several different types of dog, each to its individual purpose within the pack.

Terriers have fire and tenacity, and fit into small spaces, but they tend to use their voices only when quarry is in view. They also have a propensity for going down holes, which is tricky under today’s laws. By crossing with a small hound such as a beagle, we dilute their desire for potholing — though many dogs will try to go to ground with sufficient incentive — as well as creating a dog that bays rather more informatively on scent.

Terriers have fire and tenacity, and fit into small spaces, but they tend to use their voices only when quarry is in view. They also have a propensity for going down holes, which is tricky under today’s laws. By crossing with a small hound such as a beagle, we dilute their desire for potholing — though many dogs will try to go to ground with sufficient incentive — as well as creating a dog that bays rather more informatively on scent.

Guns on the outside of the cover being driven can tell how close they are to their quarry and from where it is likely to break. Beagle blood also means a natural desire to co-operate with other dogs. Where terriers will usually do their own thing, each on a separate line, hounds prefer to converge on one quarry to drive it out. Sometimes spaniel, usually springer, is added to the mix, to give more tractability and persistence in difficult going. Such terms are relative: I knew someone who ran a private pack of French bassets, and crossed in beagle to slow them down.

Terrier as crow decoy

When roughshooting crows, we don’t want to risk a velvet-mouthed gundog becoming a “cruncher” because it picked- up something that wasn’t dead enough. There are even times when a hard mouth is of positive value. A friend had a terrier type that was a splendid crow decoy. She looked rather like a fox, and had a mouth of iron: my friend would shoot a crow and the dog would run-in and start shredding the mortal remains. Within what seemed like seconds, other crows would arrive to mob her and be shot, while she would run gleefully from one felled corvid to another, provoking more into attacking. Despite the undoubted intelligence of crows, several would be lured in and despatched before the others realised that something wasn’t quite right, and departed.

A working wirehaired dachsund is a small hound

Another friend had a Bedlington lurcher that was adept at aiding grey squirrel destruction. He had learned not only to spot them in the branches, but also to goad them into mocking him as

he stood up on his hind legs against the tree trunk. While circling to keep the tree trunk between them, squirrels would unknowingly edge into view and range and be shot. He would then retrieve them, his terrier blood ensuring that he never got bitten.

Create a dog for a particular job

Cross-breeding is art as well as science, and sometimes what we breed for isn’t quite what we get, especially once we go away from the first cross, which is where “dogmanship” comes in. But we wouldn’t do it if it didn’t work. Long before Labradoodles and cockapoos arrived to fill a gap in the pet market, those of us using our dogs for sport and pest control knew about adding a bit of this or diluting with a soupçon of that to create a dog for a particular job that would be even better than a pure-bred.

That is not to disrespect our pure-breds, which should take it as a compliment. Without them, we would not have such excellence as a baseline.