A sound decision as moderators to be taken off licences

After years of lobbying and more than 19,000 consultation responses, the Government has finally confirmed what the shooting community has long argued – that sound moderators should be removed from firearms licensing controls

Read moreShootingUK is the definitive online destination for enthusiasts of game shooting, stalking, and country pursuits across the UK.

Gear

-

Check out the latest 825

Browning back in the game

Read more -

Gear

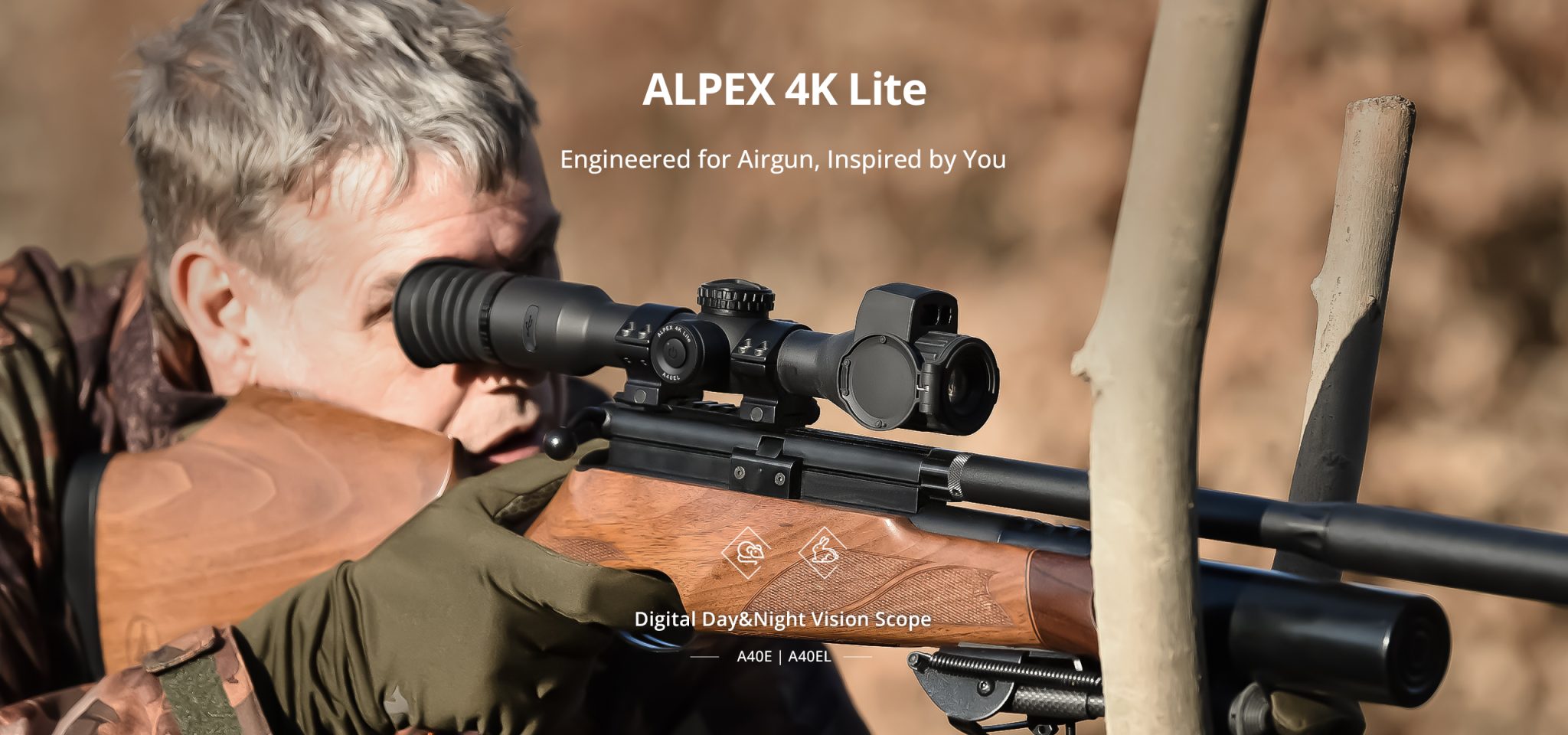

Unlocking User-Driven Innovation: Rewriting the Airgun Hunting Rules with HIKMICRO New ALPEX 4K Lite

HIKMICRO has elevated its proud commitment to airgunners to a new level with the launch of the ALPEX 4K Lite on May 22nd. This groundbreaking digital scope has been developed in response to the airgun...

By Time Well Spent

-

Gear

Unlocking User-Driven Innovation: Rewriting the Airgun Hunting Rules with HIKMICRO New ALPEX 4K Lite

HIKMICRO has elevated its proud commitment to airgunners to a new level with the launch of the ALPEX 4K Lite on May 22nd. This groundbreaking digital scope has been developed in response to the airgun...

By Time Well Spent

News

Devasting effects of keepers downing tools

A 20-year experiment highlights the dramatic decline in our red-listed birds after predator control ends, proving the vital role of gamekeepers

Read more

Kit review

Woodpigeon shooting kit reviewed

Tom Payne reviews modern woodpigeon shooting kit, from hide poles to flappers and decoys.

Read moreManage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.