Pedersoli Brown Bess musket review

Pedersoli Brown Bess musket review

Pedersoli Brown Bess musket.

The flintlock in its various forms has been with us for well over four centuries and still retains a small, dedicated following.

Indeed, if one measures success not by the size of the bag but the effort in actually achieving a bag at all, it can be argued that it is a most sporting firearm.

A considerable problem for anyone who may consider dabbling in this retro-sport, however, is finding a suitable, affordable and serviceable gun.

Sporting use

The Pedersoli Brown Bess may at first seem an odd choice, being a reproduction of a musket that saw service across the world and helped cement the fortunes of an empire.

Yet it is virtually identical to those long-barrelled 18th-century fowling pieces that remained popular even after the introduction of the shorter double-barrelled gun.

Also, with its shotgun-calibre, smooth-bore barrel, a great many Brown Besses saw secondary use after being pensioned off from military service, in private hands for sport and pot hunting.

I recently had the chance to examine a cut-down original still being used in the late-1940s for bird-scaring around orchards, some 200 years after first entering service.

A long gun

With an overall length inches short of 5ft, it can be a problem finding a gunslip to fit, or even getting the Pedersoli into the car boot.

From its brass-shod butt through the long handsome lines to the imposing muzzle, however, it is a firearm with real presence and understandable why originals are sought-after wall pieces.

At a shade over 8¾lb, it is no lightweight, but because of its length the weight distribution is actually quite good.

The point of balance is just some 9in in front of the trigger, meaning it is always going to feel muzzle-heavy and somewhat deliberate in use ? hardly the tool for consistently knocking running squirrels off branches, but for pot hunting, where results are more important than a sporting shot, it would not be a disadvantage.

The lock?s geometry

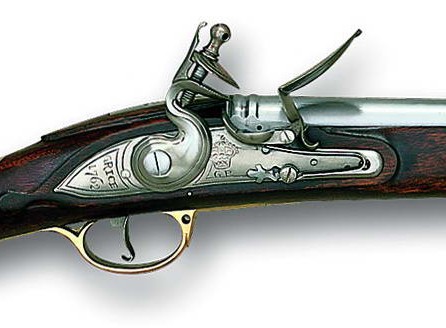

One of the most eye-catching features of the Brown Bess is the lock, with its large but elegant swan-necked cock holding the flint clamped between the jaws.

The combined frizzen and pan cover, hinged above the pan and vent (or touch hole), and large frizzen spring all add to an interesting appearance.

Something we do not get with modern guns is fundamental working parts visible on the outside and perhaps we are the poorer for it, as there is real fascination in seeing how it all functions.

While this lock was intended to be rugged and strong, it still has to follow the precise geometry essential to the reliable functioning of the flintlock.

The leather-wrapped flint has to be set so it scrapes down the frizzen face, while at the same time snapping it open to shower sparks into the pan. If the lock geometry is wrong or the flint is set incorrectly, its working life can be quite short and even basic reliability compromised, but the gun on test sparked exceptionally well ? so well it actually passed the test for a good flintlock, as later it was fired upside-down.

Internally, the proportions match the external parts, with a no-nonsense main spring that is quite massive. Each investment cast lock part is well finished and the trigger pull a proportionately heavy but fairly crisp 7½lb

Nominal 10-bore

The 42in barrel is bright polished steel, which, with an original as issued, would reputedly have been browned, but in military use was polished bright, so Pedersoli produces it in the expected antique finish, though personally I would prefer it brown.

The bore is as clean as any shotgun and, of course, without a trace of choke is true cylinder. While nominally ¾in, it actually gauged at 0.747in, just below the bottom of the 10-bore range of sizes.

Shotgun dimensions

The stock of oil-finished European walnut is quite a work of art. The barrel, ramrod pipes and even the trigger-guard tangs are secured by plain pins fitted crosswise through the stock, with screw pins through the barrel tang, rear trigger-guard tang and fore-end cap.

Two screw pins, or what were sometimes termed ?nails?, pass through the left-hand sideplate to hold the lock in place.

The brass furniture is well made, the four ramrod pipes having a particularly pleasing original look, and the heavy brass trigger-guard, thumb-rest on top of the hand of the stock and massive butt-plate are all well-executed.

While wood-to-metal fit was not quite perfect, it was up to the expected standard for most originals.

The stock wood is a most pleasing reddish-brown colour and, while essentially straight-grained ? a necessity with a long stock such as this ? would not have disgraced some breechloaders.

It was interesting to see how it measured up in relation to the dimensions expected of a shotgun.

There is no cast on the stock but this was not such a disadvantage with the very tapered comb, and 14½in from the ornate trigger to the middle of the butt came out at a fairly standard length of pull.

Drop measured slightly more than 15?8in to the tip of the comb and 2½in at the heel ? both the sorts of dimensions a shotgunner would find comfortable, and the only reason it is a little low at the front is due to the slight hogsback styling.

The hand of the stock is fairly thick, as normal with muzzleloaders, but especially so with a gun originally intended for tough usage.

Loading the flintlock

Loading a flintlock to get consistent results is often regarded as something of a black art.

The first shot prior to starting the day is simply a small charge of loose powder in the barrel, a priming charge in the pan and with the muzzle elevated for ?squibbing off? to burn any traces of oil from the bore that could interfere with ignition.

Then it can be charged properly, in this case with three drams of medium blackpowder held in place with a half-inch felt wad sandwiched between the two card wads, followed by 1¼oz of shot and a thin overshot card.

A dribble of fine powder for the pan and a couple of slaps with the palm of the hand against the stock will help ensure some enters the vent to aid ignition.

You will appreciate by now this careful preparation would put one at somewhat of a disadvantage in a ?hot? corner on a game shoot.

Stepping back in time

From the moment one hauls back the lock to full cock, it is like stepping back to another time. Is the frizzen clean, the flint set right and free from the greasy residue of powder fouling? Will it go off, or perhaps just produce a flash in the pan?

The uncertainty and distrust of earlier technology is ingrained in us, so when the first squeeze of the trigger is rewarded with a phut-BANG! and a dense cloud of greyish-white smoke, there is a distinct feeling of relief.

While the Brown Bess is never, even by the standards of the flintlock, going to be a fast lock, when everything is set just right the pan ignition and main charge blend into one glorious, rolling boom.

It is true that the puff of smoke from the pan a little in front of the face can at first be disconcerting, rather like the sparks that may sometimes be felt against the cheek, making the use of shooting glasses a good idea.

The fairly open pattern meant it was not possible to ?dust? clay pigeon, but they could be quite consistently shattered.

The technique was to swing and simply keep swinging well after the trigger was pulled.

Once this was mastered, success usually followed. The fact that the target disappears behind a smoke cloud is rather novel and because it can be a second or two before a hit or miss is registered it adds a new dimension to the sport.

Compared with the modern ejector gun, for convenience and rate of fire the flintlock is hopelessly inefficient, but following on from the success at clays a couple of rabbits ambushed one evening gave an increased sense of achievement.

Shooting the Brown Bess, it was indeed a privilege ? if only for a few days ? to be among that select band of enthusiasts that keep alive the art of using a ?flinter?.

Pros

Good reputation

Good lock

Well finished

Cons

Polished barrel

Pedersoli Brown Bess musket

£925

www.henrykrank.com