Rifle hunting – what to do after the shot is taken

It’s vital when stalking or hunting to understand the way that quarry species react to a shot, and to fess up when we could have done better, says Rudi van Kets

It’s easy to overlook certain lessons when you’re training for your hunting licence. There’s so much to learn about the correct use of weapons and how you should act during the hunt, it’s easy to forget what you’re supposed to do after you’ve shot your quarry.

This is particularly true if you are more focused on the shooting aspect of the hunt or the amount of game you manage to take over the course of the day. But a hunter’s actions in the aftermath of a shot are important, regardless of whether they are hunting deer, boar or small game.

The first point is to be honest with the handler who comes to locate the animal that has taken the bullet. I have been conducting searches like this for years now, but I am still staggered by the number of hunters who try to cover up what they have done to recover their prey after it has been hit. I can sense their concern as they follow me, knowing that every small trace the dog finds tells a different story to the one they may have told me when we first met. The evidence doesn’t lie.

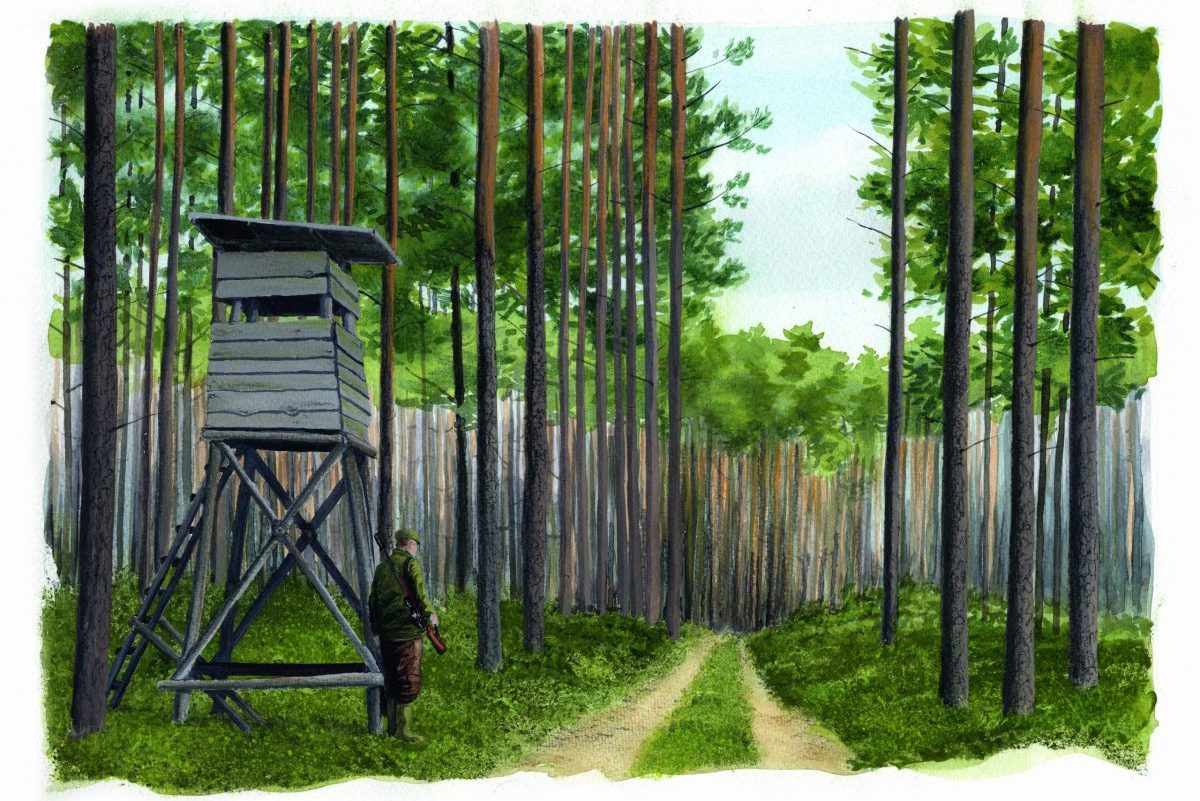

Fortunately, during our last job, the hunter was frank. As we arrived, he explained that he had positioned himself in a high seat next to a ride in the forest, hoping that a beast would pass on its way to shelter. Later, as he considered calling it a day, he heard the roar of a deer behind him. With just enough time to take up the rifle, his call stopped the deer as it trotted into the firing line. The shot was a good one, he said, but the deer bolted and disappeared in the thick cover.

Often in this situation, the hunter tries to search for the wounded beast himself or worse, tramples over the site with a group of companions and untrained dogs. However, if the hunter is honest about what has already been attempted, it helps the dog handler understand the situation. Of course, it’s even better if hunters know how to act in the first place. That is why tracking dog associations like mine have been trying for years to educate people about what they should do after their bullets hit home.

The first thing hunters should do is scrutinise what the animal does immediately after it has taken a bullet. In other words, take note of its shot response. This holds true whether they’re hunting from a high seat or taking part in a drive. Of course, these two forms of hunting are very different, and the way we study the animal’s behaviour following the shot is equally distinct, but watching where your quarry goes after you have fired is a universal rule.

Some of those we quiz after a shot are able to give an accurate account of what happened afterwards based on observation alone, but there are plenty of others who offer speculation in place of fact. Sometimes we get different accounts of the same event, depending on who we ask. It’s not dissimilar to the situation police investigators sometimes encounter when questioning witnesses.

Take your time

One of the keys to being a good observer is taking your time. Let’s imagine that we’re in a high seat and have just shot a piece of game that has momentarily disappeared from sight. Most people in this situation would immediately climb down and head over to the shot site to take a look. It’s an understandable response, but we need to train ourselves to wait a few minutes before moving.

In fact, pausing like this is the first thing all high-seat hunters should do once they see their shot hit the mark. As I was told when I first took the high seat: after you hit your target, sit quietly and smoke a cigarette, and then go and take a look. Not the healthiest advice, perhaps, but waiting for a few minutes before leaving your seat is sound guidance. If you’re lucky, your prey may drop dead more or less on the spot where you hit it but, if not, it can also try to flee only to drop down in a nearby ditch. The hunter who approaches too soon risks disturbing the injured animal, thereby causing it to run once more before collapsing a second time.

Having waited for a few minutes, hunters should move on to their second task: searching for the shot site. If the animal has been hit there are always indications: blood, hair or splinters of bone. It’s important that this task is carried out alone. You shouldn’t try to pinpoint the spot as a group, or go there one after another. And don’t let dogs near the place, especially inexperienced ones.

Too many pairs of feet walking across the area where the beast was hit can destroy important clues or even create a false trail. Once again, you can compare it to police work, where the crime scene needs to be protected until the forensics team has finished collecting all the evidence. Once a hunter has found and marked the shot site, he can move on to the third and final task: following the trail left by the animal for 50m.

Once again, our hunter confirmed that he had taken the correct course of action. After a half-hour wait he set off to search the forest for the shot site. To his surprise, he found only blood — no deer. Although it can be tempting to try to track the animal over a greater distance, particularly when there seem to be plenty of signs to show its passing, it doesn’t make the final search any easier. It’s much better for the hunter to scan the first 50m carefully and mark all the evidence he finds. Blood is especially important to note as it can be washed away by rain — although our dogs can still smell it. Marking the evidence can be done by pushing a long, slender branch into the ground or by tying red ribbons to tree boughs in a wooded area.

Experienced handler

If you still can’t see the animal lying dead after following the trail for 50m, it’s time to contact an experienced dog handler, ideally someone working with an association whose dog is trained to pick up a track. All your patient observation and careful marking of the shot site will help the handler locate your missing game quickly and efficiently.

As our hunter was unable to mark any evidence, he sat tight and waited for Jazz and I to arrive. We concluded that the shot was a good one, as we progressed metre by metre. In some places Jazz spotted blood traces; we were on the right track. The Hanoverian’s nose soon caught a scent and he indicated the deer in cover. We hadn’t seen the deer yet, there was no need for us to. The characteristic behaviour of the breed, with his tail up and neck hair in a firm comb, were clear signs that the deer was still alive.

Our hunter carefully approached to deliver a final shot. The successful recovery was aided by his honest testimony. The truth will be uncovered in any case, and there will be fewer red faces if you tell the real story from the start.