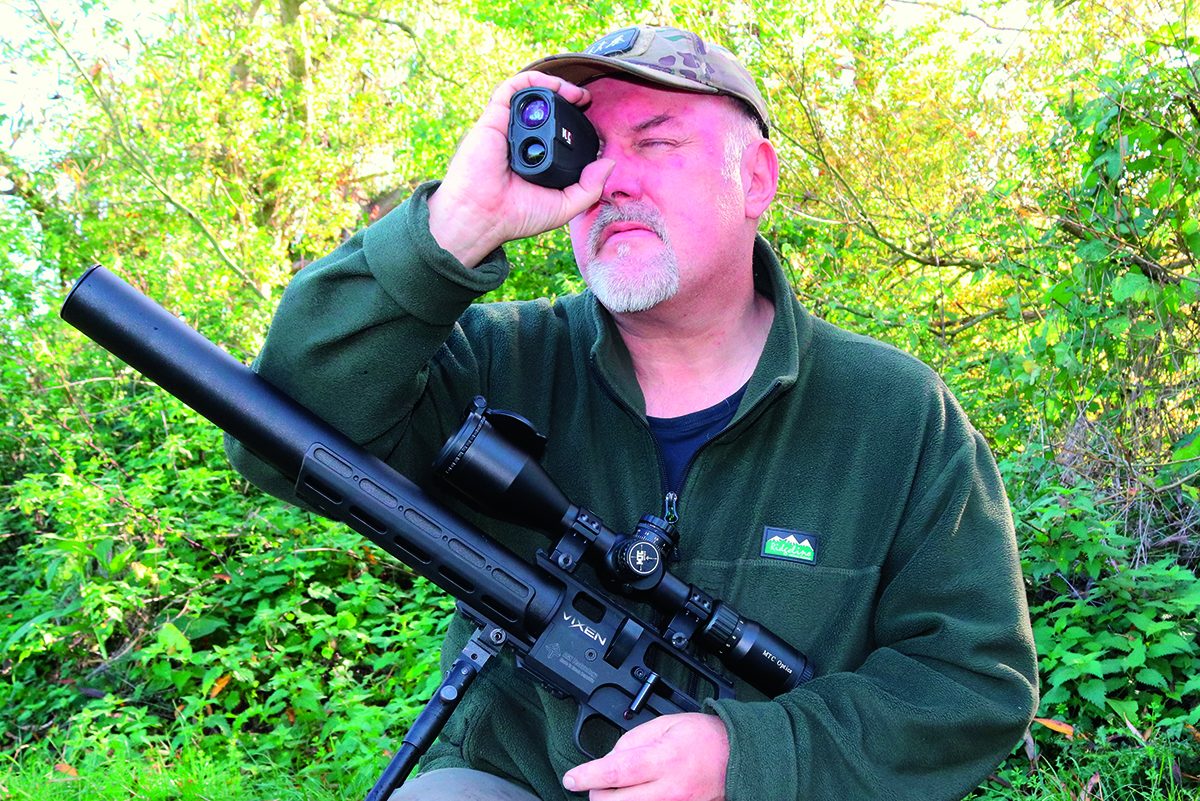

When the king shot thousands of rabbits

Once valued for fur, meat and sport, rabbits later became such a problem they were discussed in Parliament, says Simon Reinhold

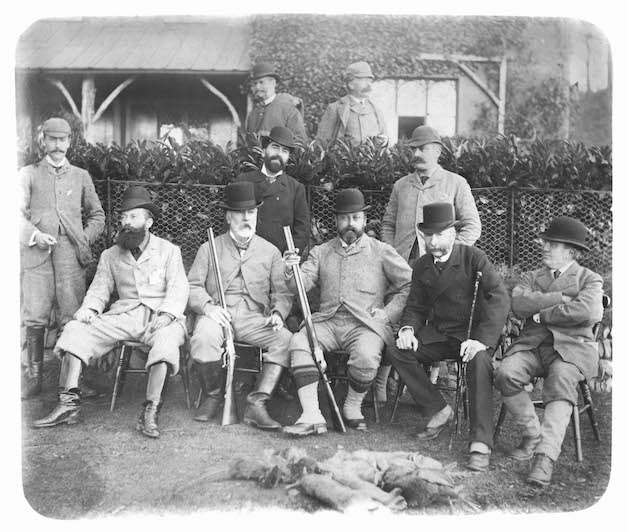

Rabbits were a popular quarry in the reign of Edward VII, pictured at Mount Edgcumbe in the 1880s’

No other animal in the British countryside has played both hero and villain like the rabbit.

The great warrens of the sandy Brecks in East Anglia were constructed to serve the fur and felt industry and cheap, plentiful meat was a bonus. The free-draining soil of Breckland was perfect for farming rabbits, but they were rarely, if ever, shot inside the warren’s boundary fence. A far higher price was commanded for rabbits that had been caught either by long-netting or ferreting.

The ruins of a warrener’s lodge on Ken Hill in Norfolk are a sign of the area’s rabbit farming history

Rabbits have been escaping farmed enclosures since their introduction by the Romans, but it was not until the 12th century and another round of importation from the Continent that they began to establish a significant feral population. Changes in farming practices during the agricultural revolution radically affected numbers of rabbits.The newly introduced crop rotation system provided year-round food and, because they can breed at six months old and can have four to six litters a year, the population exploded.

Using ferrets and a long-net is one of the traditional means of controlling rabbits

This was at a time when the economic heat had gone out of the great warrens and their fences were left crumbling. The record bag for rabbits was established at Rhiwlas, in Wales to the west of Oswestry, where rabbit farmer, shoot owner, and the organiser of Britain’s first sheepdog trials, RJ Lloyd-Price, felt it necessary to tackle his escapees.

On one of his days in 1885, nine Guns shot 5,086, with the Marquis of Ripon accounting for 920. This was to stand until 7 October 1898, when the Duke of Marlborough shot 6,943 at Blenheim in Oxfordshire.

Reducing numbers of rabbits

The game cards at Windsor Great Park also show large numbers of rabbits being shot in the reign of Edward VII, but that was only after the King had injured himself stumbling on a rabbit hole and a decision was taken to reduce the numbers. These large rabbit shoots were often driven, but walked-up rabbits with spaniels in areas of bracken was another method. The problem in both instances was getting and keeping the rabbits above ground. Ferrets could be used, but another method was to stink them out. Gamekeepers dipped a 6in square of paper or rag in a mixture that included renardine. Also known as bone oil, it was not unlike creosote and was made using animal bones rendered at a high heat. This odorous liquid would be mixed with paraffin and left in the burrow hole, which was closed up behind it. One or two holes would be left open and the rabbits would vacate the burrows overnight. On the morning of the shoot, the remaining holes would be blocked up, leaving bracken banks heaving with rabbits. The practice of leaving noxious chemicals on the ground has been illegal since 2005 and renardine itself is now banned.

Rabbits directly benefited from a gamekeeper’s activities, with predator control meaning their numbers could increase. Some keepers believed that having some foxes around meant that others were less likely to move in, so they would leave rabbits near the earths to divert the resident foxes’ attention away from the birds.

Rabbits were also an important part of early rearing and releasing, with game chicks fed a mix of finely minced rabbit and biscuit meal before commercial versions became available in the 1950s. A use was even found for rabbit skins, which were worthless in spring and summer. They were rolled up and exposed to blow flies, then the maggots were tipped out to provide a tasty snack for growing poults.

Walking-up rabbits with spaniels was used as a method of controlling numbers in the 1800s

Crop damage

During World War II, the rabbit was a serious concern and a major drain on agricultural productivity at a time when the nation was under U-boat blockade. Crop damage was estimated at £50million per year and 40% was caused by rabbits at a time when the country could ill afford it. Questions were asked in Parliament, private members bills were introduced and rabbits were even the subject of a parliamentary inquiry.

The reduction in numbers of gamekeepers (by 65% from the profession’s height) and the contraction of game shooting that had begun in World War I caused a rapid rise in rabbit numbers in the 1930s. At this time, the rabbit was regarded as a sporting object by landowners, not all of whom were fully aware of the costs they were incurring.

By the 1940s, when domestic food production had become vital, the state had declared war on the rabbit. Pest control societies were set up, which were in part responsible for successfully raising agricultural output by 5%. While the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries conducted its war of attrition, many people for whom fresh meat had become a luxury frowned on the introduction of Cymag to gas bunnies in their burrows. The rabbit was both hero and villain again. As rationing intensified during the post-war global economic slump, a rabbit was welcome in many kitchens. Many that found their way into British kitchens, however, were imported from Australia, whose plague caused the market for home-killed wild rabbits to all but disappear.

An RSPCA inspector examines a rabbit with myxomatosis

Signs of recovery

These days, in many parts of the country, rabbits are an increasingly rare commodity. The introduction of myxomatosis in Kent in October 1953, and more recently the surge of viral haemorrhagic disease, has caused the population of wild rabbits to fall catastrophically, though there have been recent signs of recovery in some places. Not 20 years ago, I relished the prospect of shooting rabbits bolting in front of the combine. A similar sporting challenge could be found as local shoots disced in their maize covers. In places where rabbits are still relatively common, this can still be done. However, Matt Smith, a shooting instructor with Calvert Sporting, says there is little to compare with roughing up rabbits over spaniels on the edge of grouse moors where rabbits are still plentiful. On the lower edges of moorland, the rough pasture that is full of sedge and rush eking out a living in the acidic soil can be a protective habitat for rabbits.

Matt says: “Some of this ‘white pasture’ is used for training spaniels and we would typically shoot with two Guns. Very occasionally you can even buy days like these.”

Experienced dogs work in close to the line of Guns and trainers. When a rabbit first flushes, it can be right under your feet. “The thickness of the cover will dictate how quickly you can get on to the rabbit,” Matt says. “I would walk with the gun over my arm and as the dog starts to look busy then the gun can come between the hands ready for a shot. You can also try to identify likely looking spots yourself.”

Matt advocates no more than quarter and half-choke for rabbits and anywhere between 28-gr and 32-gr loads, but he is definite in his choice of shot size. “You really want fives for rabbits. This matters as they get out to 40 and 50 yards and if they’ve been flushed by inexperienced dogs working further away from you, they may start at 30 yards and only begin to present a shot at 40 yards.”

Escape route

The biggest mistake he believes, is people trying to shoot too quickly. “When a rabbit is flushed, it is in flight mode straight away and can’t see its escape route. It’s likely to have a dog on its tail, so it will jink like a snipe or a woodcock. Also, this is a safety issue, as the dog will be close to the rabbit.” Matt believes that 90% of missed shots occur because the first shot is too early. Then people try to aim like a rifle with the second, resulting in a miss behind. He says the best option is to start guiding the barrel out towards a rabbit when it flushes then wait for it to pick a path.

Matt also warns that “it is easy to shoot over the top of a rabbit and you should know how your gun is set up. If it shoots 60/40, then you want to be coming through the front feet of the rabbit. It is quite an instinctive shot, but you shouldn’t just practise close rabbit targets at your local clay ground,” he cautions. “Some of the rabbits will be 40 to 50 yards away. You need to practise at distance, which will be more of a swing-through shot assessing the speed of the animal. The usual safety rules apply and you must be very conscious of the whereabouts of dogs at all times. In an ideal world, the dog will sit to flush, but that’s not always the case with young dogs.”

It is doubtful that we’ll ever see pre-war rabbit numbers again, but in certain parts of the country, as population spikes warrant it, it can be a testing day with the added bonus of watching spaniels at work.